A little while back, I made some serendipitous purchases at my local library’s annual book sale. By far the two largest books I got (for $1.50 each – watch for these things!) are The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer and The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, The Cambridge Edition Text.

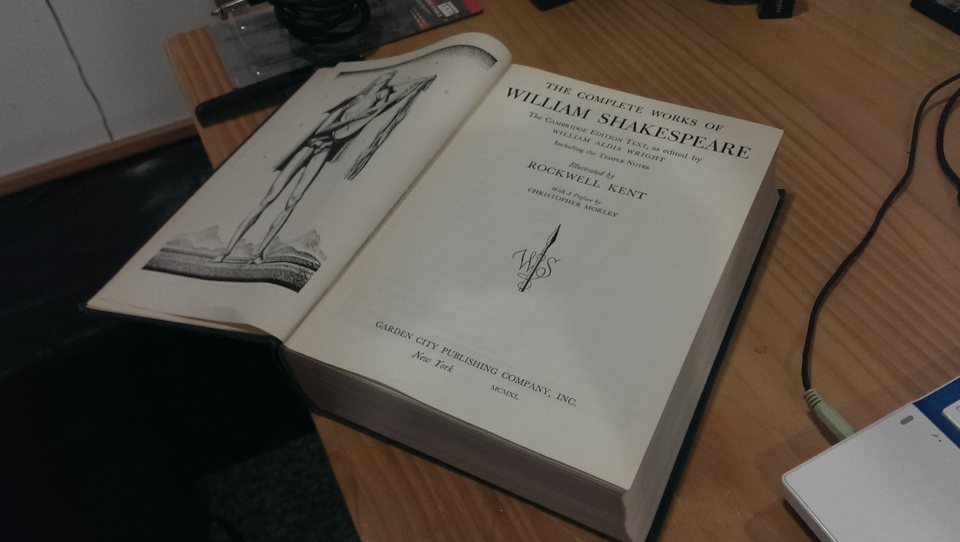

To give you an idea of what 1500 bound pages looks like, here’s a slightly tilted picture.

Now, aside from English professors and those cute nerdy girls I like so much, I doubt most people are seeing this and licking their lips in excitement. On the other hand, Willie is widely hailed as one of, if not the greatest dramatist and writer of English to have ever lived.

Why is there this disconnect? Why do the so-called experts agree that this man is so great, and the rest of us would prefer to read A Song of Ice and Fire or, well, let’s be honest, anything first published in the past 50-100 years?

Hence, this primer. An attempt, by a recent high school graduate, to explain why Shakespeare is so important for other high school students.

I’m sure my advice won’t be heard out by everyone, but for those of you who do like it, feel free to leave your comments on it.

- Yes, Shakespeare’s language is difficult. Embrace the suck!

I refuse to dress up the ugly truth. Shakespeare is not, in this day and age, immediately relevant or even comprehensible to anybody. You can look up a translation of Cicero and Ovid and those will be easier to read than the original, non-No Fear Shakespeare. I have never met somebody who can sit down, read a Shakespeare play cold, and just get it with all its hidden meanings like that.

But think about what that means. It means that he has this immense reputation not because of, but despite this difficulty. People who do work through his stuff find it so mind-blowingly amazing that they’re reduced to tears, be it of sadness or laughter.

Learning to read Shakespeare is like that boring part of first learning a language, where you’re mostly just memorizing basic semi-obvious facts. It’s only after that phase that things start to get really interesting – and with Shakespeare, oh boy, do they. - Shakespeare was never a “classic;” he’s more like a TV writer.

Believe me, after you get over the hurdle of his antiquated-but-beautiful language, this becomes a lot more obvious. In the book that I have, Macbeth takes up less than 40 pages of text in its entirety, and it’s one of the greatest tragedies ever written (not to mention I read Lady Macbeth in Marilyn Monroe’s voice – the sexiest insults ever ensue).

You don’t cover that much plot in that short a time by dragging things out. When it does look like things are being dragged out, it’s always for the purposes of characterization, or just plain epic lines.

What does that sound like? The writing philosophy of Joss Whedon. Or Steven Moffat. Or any writer of excellent television, for that matter. If it’s not advancing things, it gets cut out – so everything has some importance.

Incidentally, this is why you hear so many popular and “literary” authors alike praising Shakespeare. He’s the perfect person to model oneself on in the world of writing, because — as crazy as it sounds — his verse has just the right economy to it, every time. - Shakespeare was never a classic-ist, either. That’s how he got his reputation.

Because I love seeing famous dead people get one-upped by other famous dead people I picked up a copy of The Cult of Shakespeare at that book sale, too, and I’ve been reading it over the past 2 days with immense relish. It’s a constant gaggle of stupid things people have done over the centuries in Shakespeare’s memory (look up William Ireland and be prepared to facepalm hard).

But literature and the history of its reception always shed light on one another, and it suddenly hit me halfway through why Shakespeare’s plays were so powerful. You see, back in ancient theatre, works had to be made according to strict rules. Have a happy ending. People should get their just desserts. Don’t kill off the good guys, and give the bad guys their due.

Now, for a beginning writer who doesn’t really know what he’s doing yet, these are actually very nice principles to abide by. They let him churn out stories that aren’t exactly formulaic, but it’s hard to fuck up a story that doesn’t end with an insane ending like a father and all of his daughters dying in the middle of a foreign invasion that they themselves started because of a dumb family spat that you’d expect to be parodied in an episode of The Simpsons.

Oh, wait, that’s King Lear. My favorite Shakespeare tragedy so far. That’s where Shakespeare took things in a different direction: He simply ignored the rules of classical drama.

In doing so, his stories took on an altogether more organic form to them, and all their parts could work together to form an insurmountable whole of pathos and power. Why did this work? Because true artistic genius can’t be handcuffed like that, by rules of “unity” and “symmetry”. True genius can pull a Houdini on silly rules like that when the opportunity arises, and you’ll just sit there amazed. - Shakespeare’s characters are so well-developed we don’t always know what’s going on with them.

What? What the hell does that mean? Let me explain: There are some characters in fiction who are completely predictible. Usually, they show up in supporting roles, and if they don’t they’re a negative indicator of the quality of a work. Nobody wants to watch a show about the guy who sells Jerry Seinfeld et al. coffee at that shop, because he’s boring.

Conversely, there are some character who are a complete mystery to us – they’re so hard to pin down, they might as well just get written out of the story, because there isn’t much going for them in terms of audience appeal in the first place. As much as I love James Joyce, this is how I feel about Stephen Daedalus in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man – granted, I was much younger when I read it, but it proves that too much ambiguity can be just as bad as too much predictability.

Shakespeare, however, puts down enough detail in stone for us to love his characters, and omits enough to let us come up with our own interpretations.

Let’s take a step back and admire that for a moment: Is Hamlet just indecisive, or does he already have everything planned out from the beginning and he’s just waiting for a chance to strike? Is Lady Macbeth a cold-hearted bitch who goes crazy as divine retribution, or did she want to be that cold-hearted bitch but wasn’t really, and when she tries to be then she goes crazy? And don’t even get me started on Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

The point here is that Shakespeare’s got a knack for hitting the ‘sweet spot’ of characterization in his works. That’s why from the beginning his plays transcended their lower comedy and proved to be something more gripping.

Okay, I’m sure you’re getting as tired of reading this article as I am, but let me just reiterate: Shakespeare rewards those who put the effort in immensely. Yes, he is hard, and there’s little getting around that. He’s also awesome at what he does [uh… did], and that’s why people go so rabid about him, especially people who make reading and writing their professions.

I really hope somebody reads this, I don’t want it to disappear in the vacuum of the blogosphere.

Related articles

- ‘Nothing’ Really Matters: Is Joss Whedon Our Shakespeare? (hardinthecity.com)

- Will Power: 10 Great Shakespeare Movies (liturgicalcredo.wordpress.com)

- Review: Joss Whedon’s Much Ado About Nothing (maahinandfilms.wordpress.com)

- What Your Favorite Shakespeare Play Says About You (flavorwire.com)

- Fair play to Shakespeare, a man for all time (paulsmith.co.uk)

- Shakespeare’s Timeline (mackay6th.wordpress.com)

- Happy Birthday, dear Ben (tisnewtothee.wordpress.com)

- William Shakespeare’s Star Wars is Exactly What You Need For Your Next Geeky Houseparty (tor.com)

- Shakespeare was the Joss Whedon of his day, claims Much Ado star Alexis Denisof (independent.co.uk)

- The Shakespeared Brain (viewfrom23rd.wordpress.com)